CHS Addressing

Oh boy, this one’s gonna be a bit calculation heavy (which isn’t very fun in assembly to be honest). We are going to be starting our dive into the world of disk reading, and for that we’re going to intimately understand the drives themselves. Buckle up!

The Disk

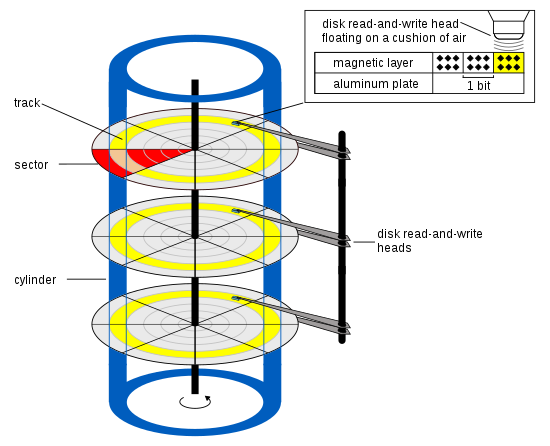

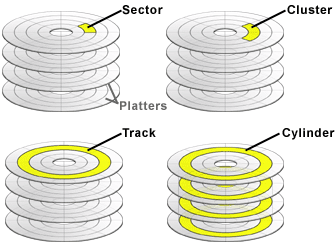

A hard drive is made of a series of spinning disks (called platters), each with either one or two read/write heads (in the case of two, there’ll be one above and below the disk to interact with both sides). Each platter has tracks going around it, with sectors making up small parts of each track. Have a look at the diagrams to get a better sense of it.

Source: Wikipedia

Source: IEB-IT Wiki

What is CHS Addressing?

CHS addressing stands for “Cylinder-Head-Sector” (which you might notice are parts of the drive!) and is a way of referring to data on the disk. You tell the disk exactly which cylinder, head, and sector you want to read from/write to, and it’ll do just that.

Alternatives to CHS

There exists an alternative form of addressing called LBA (Logical Block Addressing). It’s honestly much nicer to use, all you do is give the drive a sector number to interact with.

Why don’t we use it?

Currently, we’re emulating booting off a floppy drive. Floppy drives don’t often have a way of addressing using LBA, so we’re forced to use CHS addressing for now. We could later configure our setup to boot off a virtual hard disk, but that requires a bit of work.

The Code For Calculation

So given a linear sector number, we should be able to calculate the cylinder, head, and sector number its on if we know how many sectors per track there are and how many heads per cylinder there are. We’re going to assume that we’re using a 2880 kiB floppy with 36 sectors per track and 2 heads per cylinder. Why? This is the default for QEMU. The default for Bochs is a 1440 kiB floppy with 18 sectors per track, so our calculations will break there (don’t worry, we’ll fix that later).

Setup

Let’s define a function for this calculation, I’ll put it in utility-inl.asm. You can see that it takes the LBA-sector as its parameter, and returns the CHS values in some registers. I’ll also make some defines for the constants we’ll use, as well as temporary storage spots for the CHS we calculate.

tempCylinder: dw 0

tempHead: db 0

tempSector: db 0

; (ch cylinder, cl sector, dh head) calculate_chs(cx LBA-sector)

calculate_chs:

sectorsPerTrack: equ 36

headsPerCylinder: equ 2

Sector

Alright, now we can calculate the sector, which is simply the remainder of the division of the LBA number by the number of sectors per track, plus one (because CHS sector values are one-based, not zero-based (woooo go legacy stuff!!!)). In mathematical notation, this would look like (LBA % SPT) + 1.

Let’s have a look at the div instruction, shall we? From the docs (I’m looking at the middle row, for 16bit division), we can see that we divide what’s in the 32 bits provided by dx and ax by the value we pass in. The quotient of that gets stored in ax, and the remainder gets stored in dx. Pretty neat, huh?

.calculate_sector:

; dx is the upper half (0)

xor dx, dx

; ax is the lower half (what we pass in)

mov ax, cx

; Note: the assembler won't let us use

; sectorsPerTrack as the argument to div

mov bx, sectorsPerTrack

div bx

; Add one and store

inc dx

mov [tempSector], dl

That may look a bit complicated, but hopefully you can understand it.

Head

Moving on to calculating the head, we know that the head will only be 0 or 1, depending on if there is one or two sides to the platter. We can use the mathematical notation of (LBA / SPT) % headsPerCylinder to determine the head index. As the previous div command already put the value of LBA / SPT into ax, we can simply use that value.

.calculate_head:

xor dx, dx

; ax already contains quotient of LBA / SPT

mov bx, headsPerCylinder

div bx

; Store

mov [tempHead], dl

Cylinder

Finally, we calculate the cylinder. For this, we need to do LBA / (headsPerCylinder * SPT).

.calculate_cylinder:

; Move the LBA back into dx/ax

xor dx, dx

mov ax, cx

; Divinding by HPC * SPC

mov bx, sectorsPerTrack * headsPerCylinder

div bx

; Store

mov [tempCylinder], ax

You can look at this Wikipedia page for more detail on how this conversion happens.

Finishing it Off

The function signature we added in a comment earlier said we’d return items in (ch cylinder, cl sector, dh head). So you would think that something like this might work:

.finish:

mov ch, [tempCylinder]

mov cl, [tempSector]

mov dh, [tempHead]

ret

But alas, legacy stuff strikes again! For disk interaction, the sector number has to be encoded in just 6 bits, not 8 (which means there will be a max sector number of 63). Additionally, the BIOS wants the cylinder number to be encoded in 10 bits, like this:

cx: -- CH -- -- CL --

Cylinder: 76543210 98

Sector: 543210

As you can see, the top two bits of the cylinder value needs to go at the top of the byte which contains the sector. This can be done as such:

.finish:

; Loads the sector into cl and zeroes ch

movzx cx, byte [tempSector]

; Puts cylinder bits 76543210 into place

mov ax, word [tempCylinder]

shl ax, 8

or cx, ax

; Puts cylinder bits 98 into the top of the sector byte

mov ax, word [tempCylinder]

and ax, 0xc000

shr ax, 8

or cx, ax

; The head can be done normally

mov dh, byte [tempHead]

ret

There are a few new instructions here, but it should not be too hard to follow what’s happening. movzx (“move and zero-extend”) takes a value of a smaller size than the register and moves it in, zeroing the upper part in the process. shl and shr shift the bits in a byte left/right by a certain amount, akin to the operators >> and << in C++.

Final Thoughts

That’s it, we can now calculate a CHS tuple of values for any LBA sector. In the next chapter, we’ll look at reading from a disk and actually expanding the bootloader!

See the code in full here.

< Previous Next >